To keep the lights on, we receive affiliate commissions via some of our links. Our review process.

As many dog owners know, dogs can sadly develop cancer, just like people. This means they can get bone cancer as well. Bone cancer is usually serious but only represents around 6% of all cancers in dogs. Find out more about the symptoms of bone cancer in dogs, as well as treatment and life expectancy.

Types Of Bone Cancer In Dogs

Contents

Bone cancer in dogs can either be:

- Primary – arising from the skeletal tissues themselves (

- Secondary – stemming from cancer in another part of the body, seeded through the bloodstream (metastasis)

The treatment and life expectancy relating to metastatic bone cancer are very different depending on the original tumor. Going forward, we will focus here on primary bone cancer alone, specifically osteosarcoma, as it is by far the most common.

Osteosarcoma accounts for 85% of all bone cancers in dogs. It arises from the inside of the bone matrix itself and is quite aggressive and malignant. It most commonly affects the long bones of large breed dogs, such as the femur or the humerus, but can also emerge from any other bone, such as the skull, ribs, and digits.

It usually starts deep within the bone and grows from the inside out, slowly destroying the solid bone and replacing it with painful tumor tissue. This tissue is a lot more fragile than bone, leading to fractures with even very minor trauma. These are called “pathological fractures” and are sometimes how a bone tumor is first diagnosed.

There are other types of primary bone cancers in dogs, arising from different parts of the skeleton tissue, but they are a lot less common and are often managed quite differently than osteosarcoma.

Risk Factors

When it comes to osteosarcoma in dogs, certain factors such as breed, age, and previous medical history appear to play a predisposing role.

We know, for instance, that large and giant breeds are significantly more prone to developing osteosarcoma than dogs under 35lb (15kg). A genetic component is likely in the highest-risk breeds. These include the Rottweiler, Great Dane, St. Bernard, Irish Setter, Irish Wolfhound, Doberman pinscher, German Shepherd, Rhodesian Ridgeback, and Golden Retriever.

The average age of onset of these tumors is around seven years, but some dogs sadly experience a more aggressive form of this cancer a lot younger, approximately 18-24 months.

Osteosarcoma can also develop over time at the site of a previous fracture or chronic bone infection or as a late side effect of radiation therapy.

Symptoms

The most common signs of bone cancer in dogs are pain, lameness, and, eventually firm swelling. Signs are usually similar regardless of the kind of tumor and whether it is primary or secondary. Other symptoms will depend on the location, such as swelling of an affected limb or an eye, for example, if the tumor is rising from the skull.

There can also be signs relating to the nerves of the limb being affected, such as weakness, stiffness, and dragging. A sudden and inexplicable fracture of the limb (pathological fracture) will also strongly suggest underlying bone cancer.

Diagnosis

The steps involved in getting a diagnosis of bone cancer in dogs are usually a combination of blood work and some good quality X-rays, followed by tissue sampling and staging (looking for cancer elsewhere in the body).

- Blood work can be unremarkable, but sometimes a marker called ALP will be elevated. This also provides a basis to establish liver and kidney function.

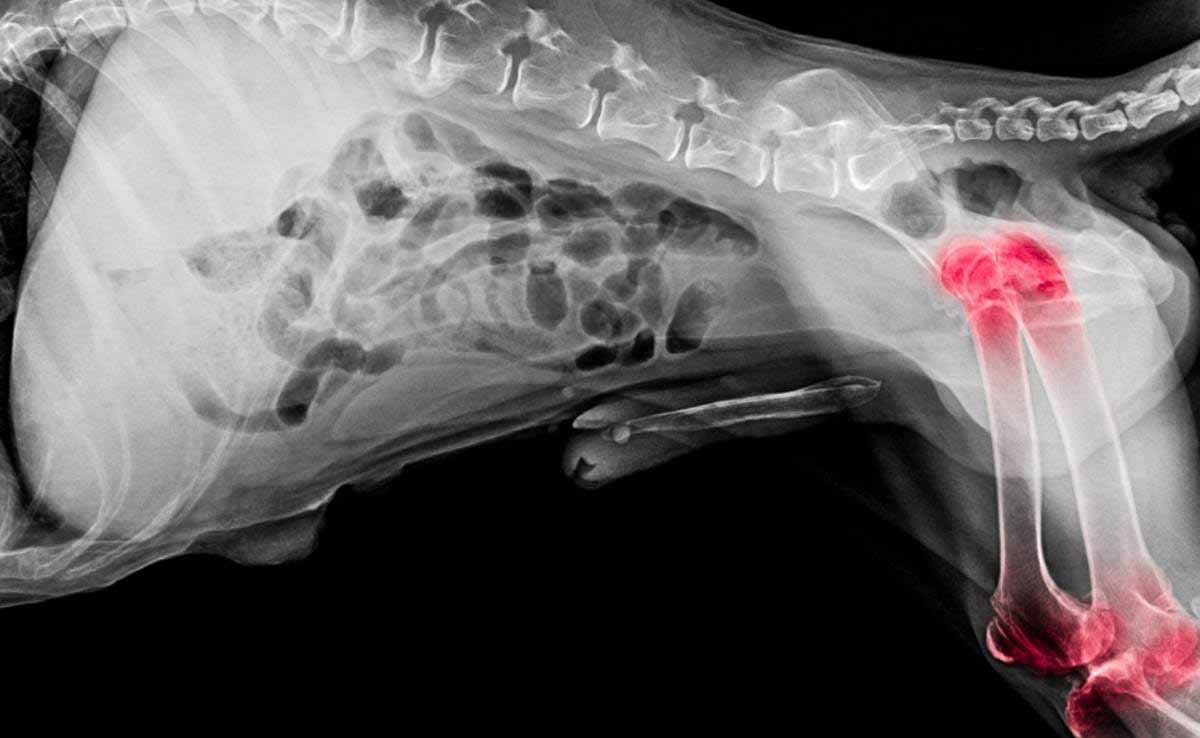

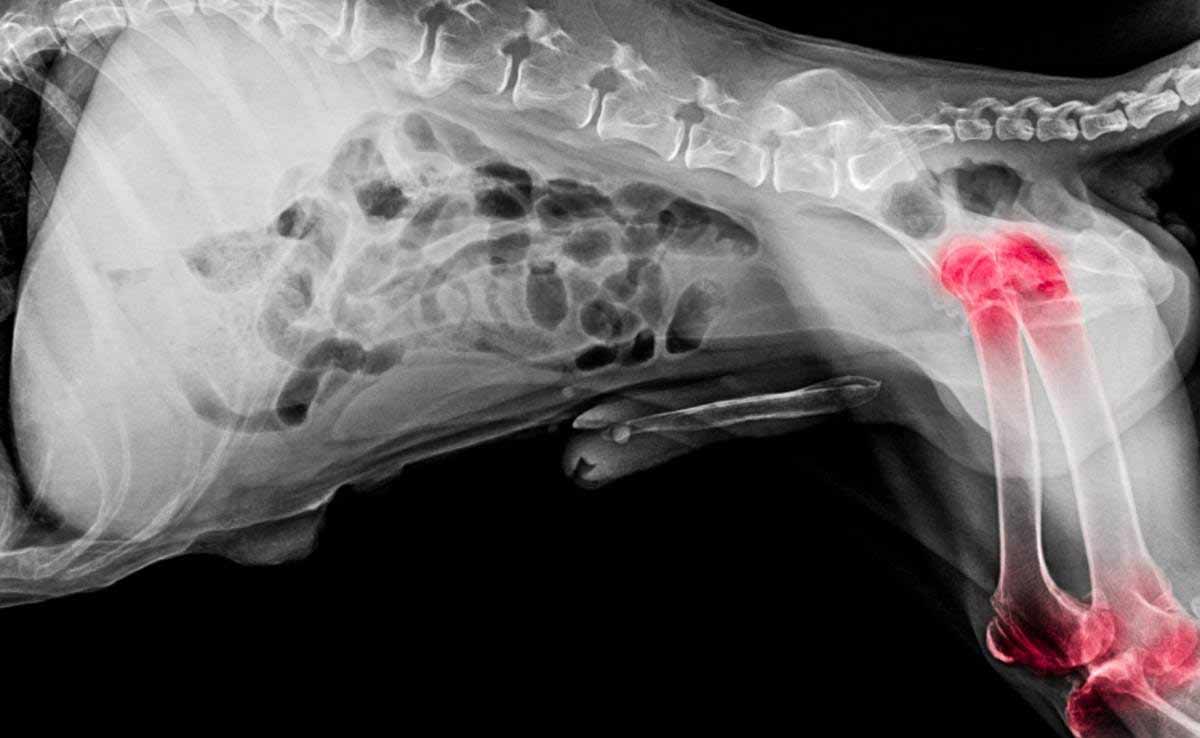

- X-rays will often be very informative and show, for instance, the bone being eaten away by the tumor or a pathological fracture. The appearance of the cancer will often be characteristic and almost completely diagnostic in itself.

- Tissue sampling is the next important step to confirm the presence of cancer since very big decisions are at stake. Sampling is often most informative through a biopsy, which requires general anesthesia, though in some cases, a needle aspiration is sufficient.

Bone cancer, in general, and osteosarcoma in particular, are usually aggressive tumors and should be assumed to have spread by the time of diagnosis. Staging is therefore important as it will help estimate survival time and whether treatment might help at all.

Treatment

Except in very rare cases, there is, sadly usually no definitive cure for bone cancer in dogs. The goal of treatment is primarily to address pain and slow down the spreading process to allow for a longer window of enjoyable quality of life.

- Pain killers – Bone cancer is usually quite painful. Though giving painkillers by mouth will help, the main step for managing pain is usually to remove the tumor altogether. If the tumor is on a limb, then amputation will usually be suggested if the dog is otherwise fit and well enough to handle it.

- Amputation – Dogs are quite different from humans: they tend to sail through managing the psychological effects of amputation. They will often just bounce back and keep on enjoying life — it is us as their owners who very understandably struggle with the implications of the missing limb. It is important to talk to your vet about this if you are feeling trepidation about this.

- Radiation Therapy – If amputation is not possible, not recommended, or not desired, radiation therapy might be helpful to consider and can greatly help both with pain management and slowing down the progression of the tumor.

- Chemotherapy – When used in addition to surgery or radiation, it often significantly improves survival time and quality of life for dogs with bone cancer. Unlike humans, the vast majority of dogs will tolerate chemotherapy very well and will maintain a very good quality of life, even during treatment.

Prognosis

Bone cancer life expectancy and progression in dogs will usually vary based on the type of cancer itself and treatment.

For osteosarcoma, less than 10–15% of dogs have detectable metastasis at diagnosis, but 90% will die within one year 11 with amputation alone due to metastasis. Survival with surgery alone or radiotherapy is usually four to five months. With added chemotherapy, the one-year survival rate goes up to 40–50%, and 20–25% of dogs are alive at two years.

Though the treatment is still usually amputation and chemotherapy, dogs with other types of bone cancer tend to have much better survival rates, usually well past three years after surgery.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can bone cancer in dogs be misdiagnosed?

Sadly, in many cases, the combination of symptoms of bone cancer in dogs’ legs and telltale X-rays is usually correct. This being said, sampling the tumor and getting a second pair of eyes on the X-rays is highly recommended before any big decisions are made.

Managing the end of a dog’s life with bone cancer

Preparing to say goodbye to our beloved furry friend is one of the hardest things we ever have to face as owners. Knowing when the time is right and navigating the space between enjoying quality time and prolonging their life at the cost of suffering can be hard. Vets are there to help, and a good rule of thumb is to look at whether a dog can move around mostly pain-free, can enjoy most of its daily activities, including eating, can use the toilet easily when needed, and be able to rest comfortably, free of nausea, pain, or difficulty breathing. Most owners will just know when their dog is no longer enjoying life the way they should.

How to prevent bone cancer in dogs? What about spaying and neutering?

There has been a lot of controversy and contradiction surrounding the topic of neutering and spaying dogs at a young age and increased risk of cancer. The matter is fairly complex: while we know desexing certain large breed dogs at a young age can be involved in cancer development, the overall survival of dogs (even breeds at risk) seems to be consistently higher when desexed. This means there is no simple or one-size-fits-all answer. The best approach for dog owners trying to decide whether and when to neuter or spay their dog would be to look at this with their veterinarian very much on a case-per-case basis.

What about bone marrow cancer in dogs?

Bone marrow cancer in dogs is quite different from skeletal bone cancer. Rather than a physical tumor growing and overtaking bone tissue, bone marrow cancers usually spread throughout the whole bone marrow and affect the production of cells that get released into the bloodstream, usually cells that are part of the immune system. A few examples are multiple myeloma, leukemia, or occasionally lymphosarcoma (lymphoma).

Bone marrow cancer in dogs is usually diagnosed through a blood test, but a bone marrow biopsy can still be required to pinpoint the exact nature of the issue and how to best treat it.

Other Signs Of Canine Cancer

Bone cancer, especially osteosarcoma, is not extremely common but is sadly one of the worst cancers a dog can get. Treatment is usually geared towards pain control, slowing down the progression of cancer, and helping owners and their furry friends get as much quality time together as possible. Dogs can also have other general signs of cancer which you can learn more about those in our dog cancer article.

Tagged With: Cancer, Orthopedic